The photos you're brave enough to take - 10 Qs with Ella Tan

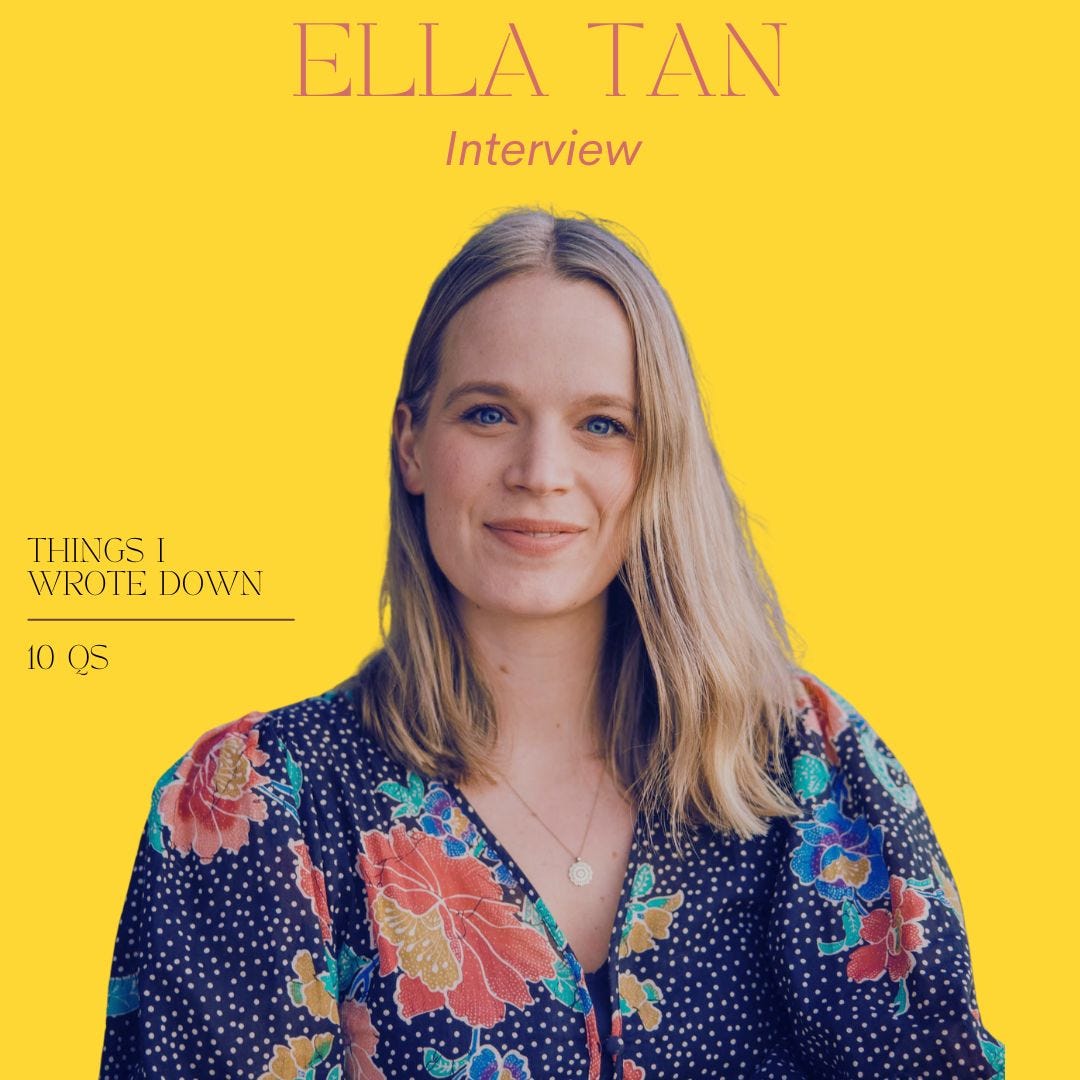

Meet the Australian writer and photographer who is one of the judges for the TIWD poetry contest

Ella Tan has travelled to some of the most vulnerable populations on earth to capture important moments. Guess what she found? Dignity. Imagination. Even when it scared her.

In this interview, Ella shares why we can’t overlook shadows in our search for beauty, how creative tools and life’s purpose spills over into the practical—like feeding the hungry—why slowness can be good for creativity in a fast-paced world, and the photographs she didn’t take.

Your work as a writer and photographer has taken you to places in the world many people will never see. What are some of the places you’ve been that you never would have expected to visit or write about?

I’m constantly being surprised by the twists and turns of where photography, writing and storytelling has taken me! I don’t think I am a naturally adventurous person and can even sometimes feel overwhelmed travelling to new places. I’ve visited the Sahel Desert during a drought, tombstone dwellings in the Philippines, a refugee camp bordering Thailand and Myanmar, a prison in Kenya, a fishing community in Indonesia and the tea field plantations in Bangladesh. I’ve also visited the newest country in the world, South Sudan, within a few weeks of it officially existing, and the country with the fastest-shrinking population in the world, Moldova.

There’s a Dr. Seuss book, Oh, the Places You’ll Go! and one page reads, “All Alone! Whether you like it or not, Alone will be something you’ll be quite a lot. And! When you’re alone, there’s a very good chance, you’ll meet things that scare you, right out of your pants. There are some down the road between hither and yon, that can scare you so much, you won’t want to go on.” Let’s just say that I can relate!

I have spent years searching for colour and creativity in some of the most vulnerable places on earth. The ways that people express their dignity, imagination and care has kept me believing that the face of God is visible in anyone.

Ella is one of the judges of the Things I Wrote Down Poetry Contest this year,

lending her expertise to select the winning poems.

How did you land in humanitarian work in the first place?

I don’t remember an exact time when I thought “I want to work in the humanitarian or aid sector” – I think that probably just became clearer and clearer over time. I had a natural curiosity and excitement about the wider world, cultures different to my own and places that I’d never been to. Growing up, my family sponsored children in Gambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and other countries. I loved reading the girls’ letters and writing back to them. I wrote on pale blue, thin airmail paper and enjoyed these friendships that spanned many kinds of boundaries.

When I was 12, I read about children who had been recruited to fight as soldiers in the decade-long Sierra Leone civil war and decided to swim a mile to raise money for an organization working to rehabilitate child soldiers. I remember feeling so free in the water; such a contrast, I imagined, to the children who were so trapped by violence or exploitation.

“The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet,” wrote author Frederick Buechner. My delight is found in creating, making, writing, photographing and it’s been an exciting journey to figure out how to use these tools to serve others and to feed the hungry.

How has this view into the word—insights into its wide array of beauty and its vulnerability—informed your writing?

My writing and photography is defined by a paradoxical overlap of beauty and hunger, longing and loss, hope and fragility, colour and scarcity, which fill our human experience and shape our world.

I hope I’m never too simplistic or bent on searching for beauty, that I overlook the shadows. I also hope that I’m never too afraid, cynical or burned out that I don’t see beauty, light, colour, meaning or hope.

Do you remember when you wrote your first poem? What was it and what happened?

I don’t remember exactly! It was probably as a very young child and almost definitely about fairies, bluebells, gemstones or tea parties!

I do remember the first time I started thinking of myself as a poet, though. Only recently, after around twenty years of writing for an audience (albeit a small one, often!) I realized that even if I didn’t always write poetry, I thought like a poet, saw like a poet, and moved through the world making connections or observations like a poet. I’ve come to accept that even if I’m not always writing or creating, I will always be a writer or an artist.

You elevate the importance of the slowness of the creative process in your article about the altered sketchbook project you’ve worked on with your sister and a friend for over a decade. Can you share about the significance of that project and what you’ve learned about collaboration and creative pace since that book has exchanged hands across oceans?

Since writing that post, our book is almost full now! I think I’m most proud of the longevity of this project. We’ve kept at it for over twelve years now. We also didn’t start this project to share with an audience (except each other) and while that’s changed now, something about that privacy felt safe and comforting – we were free to explore creative techniques and tools that were new to us.

Life circumstances have forced us to take this project slowly, as well as the act of posting the book. I’ve had to accept that with so much of my personal writing and art, between parenting and full-time work, projects will just come together slower in certain seasons but that slowness can be good especially when contrasted with such a fast-paced digital environment.

How similar (or different) is your approach to taking a photograph to writing a poem? How defined is your personal creative process?

It’s probably quite a similar process.

#1. Something catches my attention.

Something makes me stop, makes me question or makes me feel something deeply.

#2. I narrow my sight and focus

I look through a viewfinder and move closer. I research and reflect around that first observation. I read around the subject widely (warning: this stage can sometimes get obsessive!) and I consider why my attention was held in the first place.

#3. I lift my eyes and look around

I connect that thought, poem or image to a wider context. I think about how a small moment or object would look from a different angle, from as close as a microscope slide to as distant as outer space. I weigh up how others might perceive that first moment that held my attention. I think about how others would view a certain photograph from their own context.

#4. I edit for others

If the work will go public, I edit it to serve an audience. Most of my first drafts would make sense to only me! With my images, I’ll think about whether the image is clear, honest, unique, dignifying and engaging. With my writing, I’ll edit for sense, clarity, accuracy and whether the piece makes sense. When I write, I keep the same three people in mind. I imagine ideating and develop ideas with one person (and occasionally may call them in real life), I write with another in mind, I edit with another in my mind.

What work from your creative portfolio are you most proud of so far?

Together with my husband, who is also a filmmaker and a photographer, we worked on an assignment that was almost two years long in collaboration with CARAD (The Centre for Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Detainees) here in Perth, Western Australia. The films we made are now a permanent exhibit in the Connections gallery in the WA Boola Bardip Museum, Perth.

The videos tell the stories of refugees and asylum seekers who call WA ‘home’. I loved the long-term nature of the project and the community participation. I had my own prejudices and assumptions challenged many times throughout the project.

Do you have “one that got away”—a photograph or story you weren’t able to capture that you wish you had?

There are so many photographs I wish I’d either been brave enough to take, or didn’t take for good reason. I used to keep a written, descriptive record of ‘all the photographs I didn’t take’ but the list grew too long!

Working with marginalised or vulnerable people there are simply some situations where it feels too brash, undignifying or insensitive to make certain images, or I feel in that moment that it wouldn’t honour that person. I think this varies a lot depending on what kind of photographer you are and what’s in front of your camera. There have also been moments I wish I’d taken more creative risks with an image and returned home or looked through an assignment and felt a bit of regret that perhaps I didn’t do someone’s story justice.

I think of one personal assignment I worked on over ten years ago, with Ed, a blind goat farmer who lives on a remote island on the Southwest Coast of Ireland. The images are not exceptional or spectacular, but I learned so much about myself as a photographer in the process. I’d love to go back and re-shoot this whole story with the technical skills I have now.

What’s the best piece of advice about writing that you’ve received, given, or that you hold onto?

Probably Anne Lamott, in Bird by Bird:

If something inside of you is real, we will probably find it interesting, and it will probably be universal. So you must risk placing real emotion at the center of your work. Write straight into the emotional center of things. Write toward vulnerability. Risk being unliked. Tell the truth as you understand it. If you’re a writer you have a moral obligation to do this. And it is a revolutionary act—truth is always subversive.

What advice would you give to others who want to pick up a camera or pen to document what they witness in the world?

No one sees the world like you see it. Practice paying attention with your eyes, focussing in, then widening your gaze.

In a world saturated with images, information and opinions, I’ve wondered whether images, words, and art can still bring peace during conflict, alleviate poverty or help someone to heal?

I believe there is still a chance they can.

About Ella Tan

Ella Tan is a Perth-based humanitarian storyteller, writer and photographer. Her humanitarian work has been published in leading global outlets, including BBC, Marie Claire, Elle, Psychologies, The Australian and New Zealand’s Listener.

In 2020, she completed a collaborative project commissioned by the newly opened WA Museum Boola Bardip, sharing the stories of six refugees and asylum seekers in Perth, Western Australia. The exhibit was awarded the winner of the Research Category for the 2021 Australian Museums and Galleries National Awards.

Her career working in a in remote and vulnerable communities around the world, started after winning the Oxfam Photography Prize for Women in 2013. The award provided assignment work in Chad’s Bahr-el-Gazel desert region, affected by climate change and successive droughts.

Her personal writing is represented by US-based agent, Don Pape from Pape Commons. She was awarded the KSP Poetry Prize for an Unpublished West Australia poet in 2022. Follow her on Substack at The Honeyeater Press.